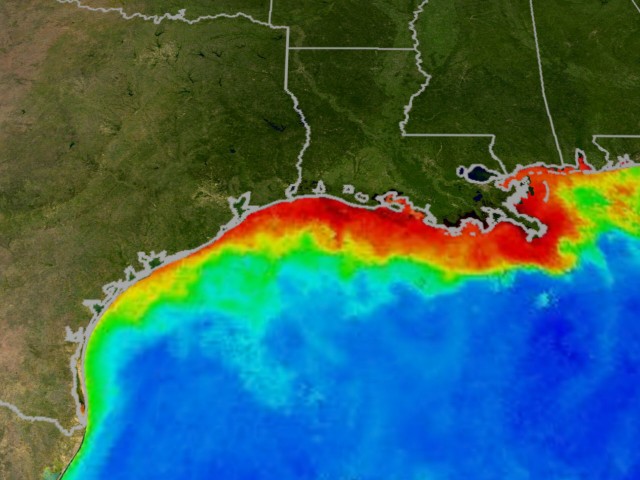

This year’s Gulf of Mexico dead zone, a mass of water depleted of oxygen that starves marine life, will encompass approximately 5,898 square miles, which is about the size of Connecticut. Although the dead zone is categorized as average in size, it is by no means normal.

The Union of Concerned Scientists note that dead zones or hypoxic zone can be created naturally or by human activity. These particular dead zones are usually coastal areas that threaten marine life and are spurred by high levels of pollutants, such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

The toxins seep into the soil or spill into the bodies of water and are consumed by algae, bringing about their demise. The algae carcasses deteriorate in the water, thereby causing other marine organisms to suffocate.

Welcome to the dead zone

Russell Callender of the National Ocean Service told the Tech Times, “Dead zones are a real threat to gulf fisheries and the communities that rely on them. We’ll continue to work with our partners to advance the science to reduce that threat. One way we’re doing that is by using new tools and resources, like better predictive models, to provide better information to communities and businesses.”

The second largest dead zone in the world is expected to be the one at the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi River empties into the gulf, among other bodies of water, that cut through the Corn Belt and other major agricultural areas of the U.S.

It has been a damp spring for the bulk of the Midwest. While it is certainly the case that rainfall contributes to the size of the dead zone, so do farming practices, which are well within human control.

Figures from USGS estimate that approximately of 146,000 metric tons of nitrate and 20,800 metric tons of phosphorus trickled down the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers and emptied into the Gulf of Mexico in May 2016. This is around 12 percent greater than the long-term average for nitrogen and about 25 percent greater than the long-term average for phosphorus.

USGS oversees more than 2,700 real-time stream gauges, 60 real-time nitrate sensors and gathers water quality information at long-term stations dotted across the Mississippi River basin to keep tabs on how nutrient loads change overtime, reports FIS.

“By expanding the real-time nitrate monitoring network with partners throughout the basin, USGS is improving our understanding of where, when and how much nitrate is pulsing out of small streams and large rivers and ultimately emptying [in] to the Gulf of Mexico,” said Sarah J. Ryker, Ph.D., acting deputy assistant secretary for water and science at the Department of the Interior.

“The forecast puts these data to additional use by showing how nutrient loading fuels the hypoxic zone size,” she added.

The scorn of the Corn Belt

A major problem with conventional farming, particularly in the Corn Belt, is that the main crop only grows from April/May to September/October when harvested. During the winter and spring, the soil is bare and vulnerable to phosphorus and nitrogen loss.

One effort to curb the runoff problem is called the “4R stragety,” which uses fertilizer at the right time and place. Although these practices can help minimize water pollution, they are likely not enough to address the problem at hand.

An environmentally friendly approach to farming would be to protect the soil all year, which could help decreased water pollution and the size of the dead zone. However, farmers are encouraged not to invest their efforts on such practices because of various farm policies that reward cropping patterns centered on short-term results.

The definitive size of the 2016 Gulf dead zone will be disclosed in early August after a monitoring survey conducted between July 24 and August 1 is complete.

Sources: